I saw at the cinema

I saw

Nous sortons du rêve comme nous quittons une salle de cinéma : dans un état entre l’éveil et l’endormissement. Malgré des moyens de création distincts, le rêve et le cinéma partagent une même logique d’enchaînement. Le cycle de sommeil humain se compose généralement de quatre ou cinq phases, au sein desquelles le rêve émerge, sur une durée de 90 à 120 minutes — un temps relativement proche de celui d’un long-métrage.

Les images se superposent, s’entrelacent. Le rêve dresse un état des lieux du monde, à travers un montage de souvenirs vécus ou fictionnalisés. Nous y sommes à la fois réalisateur, acteur et spectateur. Tantôt passifs, tantôt actifs, nous percevons autant que nous sommes perçus.

Ce rapport trouble entre perception et subjectivité montre combien les images, loin d’être fixes, se déplacent sans cesse, modelées par notre expérience et nos souvenirs. Cette porosité entre image et mémoire invite à penser le cinéma — et par extension la pratique artistique — comme un lieu de reconfiguration du quotidien et de la fiction.

C’est dans cette continuité que s’inscrit Opening Night, une exposition pensée à deux voix, par Kira Gyngazova et Adrien Tinchi, où l’intime et la mise en scène s’articulent dans un espace partagé, guidé par des logiques de montage, de déplacement et de point de vue. L’installation On Horizon, placée au centre de l’espace, suggère que le sommeil et le cinéma ne sont pas une suspension de l’attention, mais un terrain actif d’observation. Observer une image comme se sentir observé par l’image, c’est admettre d’être influencé. Une femme est allongée sur le lit. C’est un regard posé et projetée que nous voyons.

Le lit devient alors un écran, un seuil entre la veille et l’endormissement, comme l’évoque la pièce I was tired so I decided to wake up (j’étais fatigué alors j’ai décidé de me réveiller). Une compréhension inédite du monde surgit, au moment même où l’autre se repose. Elle peut prendre corps dans un livre dont les pages deviennent surface d’expérimentation. Là, l’écriture se retire peu à peu pour laisser place à des silences, et le sens affleure dans les vides, dans les marges. Une forme de poésie noire, presque spectrale, naît par soustraction — en effaçant pour mieux révéler. Ce principe d’effacement se poursuit dans Soundtrack for today, une installation sonore construite autour d’un protocole de disparition. Chaque jour, une composition originale est diffusée en boucle via une pédale d’enregistrement ; à la fin de la journée, elle est effacée, remplacée par une nouvelle pièce. À rebours de l’archive, ce qui a été entendu ne pourra plus l’être. Le son, fugitif, ne survit que dans la mémoire de celui ou celle qui l’a traversé — comme un rêve au réveil, ou une image engloutie dans le montage.

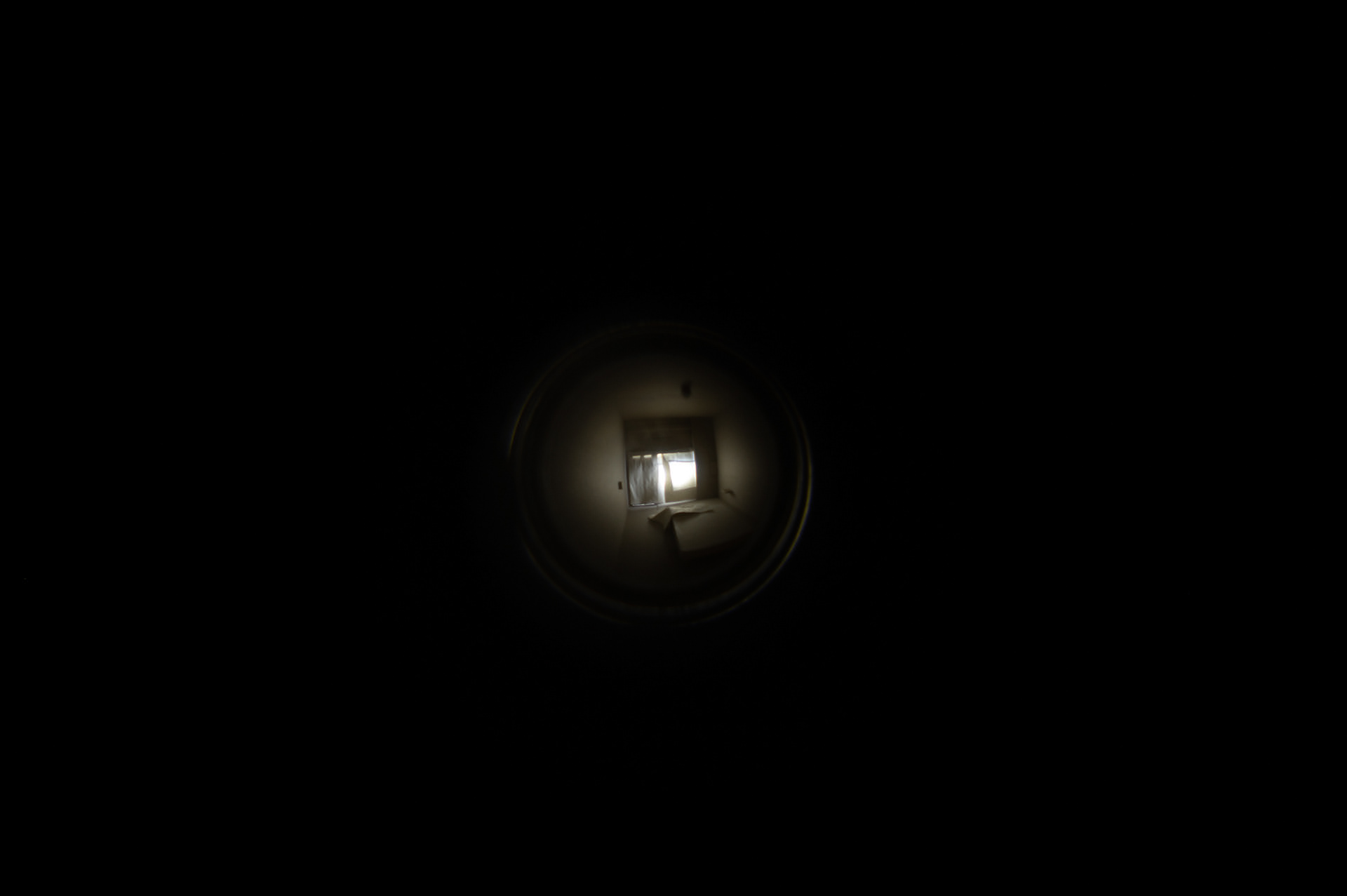

Certaines œuvres apparaissent en marge, à la lisière du visible. 3,8mm se regarde à travers un œil-de-bœuf. Ce que l’on voit : une maquette, observée depuis un point de vue que l’on ne peut jamais occuper. Le regard s’y exerce à distance, filtré par une focale étrangère — comme pour rappeler que toute vision est déjà construite, mise en scène.

Ailleurs, une photographie trouvée figure un geste suspendu. Là encore, il s’agit d’un regard porté sur le seuil d’un événement, dans l’instant qui précède son basculement.

Ce qui subsiste n’est pas toujours ce qui se montre. Jouer et rejouer sa place, car toute image suppose un jeu. Et c’est peut-être ce jeu-là, au fond, qui rend poreuse toute frontière entre ce que l’on vit et ce que l’on imagine.

I saw

Nous sortons du rêve comme nous quittons une salle de cinéma : dans un état entre l’éveil et l’endormissement. Malgré des moyens de création distincts, le rêve et le cinéma partagent une même logique d’enchaînement. Le cycle de sommeil humain se compose généralement de quatre ou cinq phases, au sein desquelles le rêve émerge, sur une durée de 90 à 120 minutes — un temps relativement proche de celui d’un long-métrage.

Les images se superposent, s’entrelacent. Le rêve dresse un état des lieux du monde, à travers un montage de souvenirs vécus ou fictionnalisés. Nous y sommes à la fois réalisateur, acteur et spectateur. Tantôt passifs, tantôt actifs, nous percevons autant que nous sommes perçus.

Ce rapport trouble entre perception et subjectivité montre combien les images, loin d’être fixes, se déplacent sans cesse, modelées par notre expérience et nos souvenirs. Cette porosité entre image et mémoire invite à penser le cinéma — et par extension la pratique artistique — comme un lieu de reconfiguration du quotidien et de la fiction.

C’est dans cette continuité que s’inscrit Opening Night, une exposition pensée à deux voix, par Kira Gyngazova et Adrien Tinchi, où l’intime et la mise en scène s’articulent dans un espace partagé, guidé par des logiques de montage, de déplacement et de point de vue. L’installation On Horizon, placée au centre de l’espace, suggère que le sommeil et le cinéma ne sont pas une suspension de l’attention, mais un terrain actif d’observation. Observer une image comme se sentir observé par l’image, c’est admettre d’être influencé. Une femme est allongée sur le lit. C’est un regard posé et projetée que nous voyons.

Le lit devient alors un écran, un seuil entre la veille et l’endormissement, comme l’évoque la pièce I was tired so I decided to wake up (j’étais fatigué alors j’ai décidé de me réveiller). Une compréhension inédite du monde surgit, au moment même où l’autre se repose. Elle peut prendre corps dans un livre dont les pages deviennent surface d’expérimentation. Là, l’écriture se retire peu à peu pour laisser place à des silences, et le sens affleure dans les vides, dans les marges. Une forme de poésie noire, presque spectrale, naît par soustraction — en effaçant pour mieux révéler. Ce principe d’effacement se poursuit dans Soundtrack for today, une installation sonore construite autour d’un protocole de disparition. Chaque jour, une composition originale est diffusée en boucle via une pédale d’enregistrement ; à la fin de la journée, elle est effacée, remplacée par une nouvelle pièce. À rebours de l’archive, ce qui a été entendu ne pourra plus l’être. Le son, fugitif, ne survit que dans la mémoire de celui ou celle qui l’a traversé — comme un rêve au réveil, ou une image engloutie dans le montage.

Certaines œuvres apparaissent en marge, à la lisière du visible. 3,8mm se regarde à travers un œil-de-bœuf. Ce que l’on voit : une maquette, observée depuis un point de vue que l’on ne peut jamais occuper. Le regard s’y exerce à distance, filtré par une focale étrangère — comme pour rappeler que toute vision est déjà construite, mise en scène.

Ailleurs, une photographie trouvée figure un geste suspendu. Là encore, il s’agit d’un regard porté sur le seuil d’un événement, dans l’instant qui précède son basculement.

Ce qui subsiste n’est pas toujours ce qui se montre. Jouer et rejouer sa place, car toute image suppose un jeu. Et c’est peut-être ce jeu-là, au fond, qui rend poreuse toute frontière entre ce que l’on vit et ce que l’on imagine.

“Talking about dreams is like talking about movies, since the cinema uses the language of dreams; years can pass in a second and you can hop from one place to another. It’s a language made of image. And in the real cinema, every object and every light means something, as in a dream.”

—Federico Fellini

I saw at the cinema

I saw

I saw

We emerge from a dream as we leave a movie theater: in a state suspended between waking and falling asleep. Despite their distinct means of creation, dreams and cinema share a similar logic of sequencing. The human sleep cycle generally consists of four or five phases, within which dreaming occurs over a span of 90 to 120 minutes—a duration relatively close to that of a feature film.

Images overlap and intertwine. The dream offers a kind of inventory of the world, assembled through a montage of lived and fictionalized memories. Within it, we are at once director, actor, and spectator. Sometimes passive, sometimes active, we perceive as much as we are perceived.

This troubled relationship between perception and subjectivity reveals how images, far from being fixed, are in constant motion, shaped by our experience and our memories. This porosity between image and memory invites us to consider cinema—and, by extension, artistic practice—as a site for the reconfiguration of the everyday and of fiction.

It is within this continuity that Opening Night takes shape, an exhibition conceived in dialogue by Kira Gyngazova and Adrien Tinchi, where intimacy and staging intertwine within a shared space, guided by logics of montage, displacement, and point of view. The installation On Horizon, placed at the center of the space, suggests that sleep and cinema are not a suspension of attention, but an active field of observation. To observe an image and to feel observed by it is to acknowledge being influenced. A woman lies on the bed. What we see is a gaze that is both placed and projected.

The bed then becomes a screen, a threshold between wakefulness and sleep, as evoked by the piece I was tired so I decided to wake up. A new understanding of the world emerges at the very moment the other rests. It can take shape in a book whose pages become a surface for experimentation. There, writing gradually withdraws to make room for silences, and meaning surfaces in the gaps, in the margins. A form of dark, almost spectral poetry is born through subtraction—by erasing in order to reveal.

This principle of erasure continues in Soundtrack for Today, a sound installation built around a protocol of disappearance. Each day, an original composition is looped through a recording pedal; at the end of the day, it is erased and replaced by a new piece. Against the logic of the archive, what has been heard can no longer be heard again. Sound, fleeting, survives only in the memory of the one who has passed through it—like a dream upon waking, or an image swallowed by the edit.

Some works appear at the margins, at the edge of visibility. 3.8 mm is viewed through a bull’s-eye window. What one sees: a model, observed from a point of view that can never be occupied. The gaze is exercised at a distance, filtered through a foreign lens—as if to remind us that every act of seeing is already constructed, already staged.

Elsewhere, a found photograph depicts a suspended gesture. Once again, it is a gaze directed at the threshold of an event, in the instant just before it tips over.

What remains is not always what is shown. To play and replay one’s position, for every image implies a game. And perhaps it is this very game, ultimately, that makes every boundary between what we live and what we imagine porous.

“Talking about dreams is like talking about movies, since the cinema uses the language of dreams; years can pass in a second and you can hop from one place to another. It’s a language made of image. And in the real cinema, every object and every light means something, as in a dream.”

— Federico Fellini

— Federico Fellini